OK there’s no point beating around the bush here. Sunday’s election result, while expected, has hit me like a ton of bricks. Georgia Meloni’s victory is going to have terrible consequences for women, racialised groups, queer people and migrants of all kinds, and as such - by definition - society as a whole. There’s little doubt that ultra-conservative, anti-democratic policies are on the way; and civic space is now under threat. That danger is real. At the same time, it’s worth remembering the picture can still be (much) worse or (much) better than it is right now. I’ve read lots of comments from people saying it’s “time to leave Italy” or “jump ship” or whatever else. I get the sentiment. But for anyone who cares about democracy in this country, or anywhere else for that matter, there’s work to be done that goes way beyond individual life choices. That’s why in this edition of the newsletter I want to break from my regular format to dive into a few nuances of the results. Because while the road ahead is certainly uphill, looking a little more closely at the details it’s far from insurmountable.

I: Meloni is, to a certain extent, nothing new

Don’t get me wrong, this isn’t meant to be particularly comforting. But it’s important to remember from the offset that Italy has been struggling with xenophobia and democratic decline for at least three decades. Neo-fascist groups have long been weaselling their way into power, from the National Alliance MPs, who were part of various Berlusconi cabinets, to other ‘sub-sects’ of militants who disguised themselves within apparently moderate post-Christian Democratic centrist parties. Meloni herself has been representing far-right positions for years in and in close proximity to government. So while the BBC, Guardian, New York Times etc have only now begun panicking, she and her ideas are hardly new. The moment we are facing, to quote my friend and colleague Alberto Alemanno, is certainly “a visceral crystallization of ongoing regressive trends”, but it is not a “sharp turn to the right.”

II: Her victory was hardly resounding

Fratelli d’Italia is an alarming party in many respects, but it has no reliable grassroots. Most Italians voted for Meloni on the basis that she was the only major party leader not to have propped up the Draghi government; they wanted to defy what they saw (wrongly) as liberal “scaremongering.” Her overall result of 26% is not, however, a ringing endorsement. True, this is a remarkable jump from 4% in 2018 but it’s also far less than winning parties usually get in Italy. In 2008 Berlusconi comfortably obtained 38% of consensus, and the Five Star Movement won 32% just four years ago in 2018. With her coalition comprised of two notoriously untrustworthy parties, both of which supported a centrist pro-EU administration just a few months ago, Meloni cannot afford to rely on anybody. Her government, much like her base, is fragile and fickle.

III: The combined centre and left won more votes than the entire right-wing coalition

You’d be forgiven for having missed this in the international coverage but if you look at the actual final result of the vote it’s true: the combined result of the centre and left parties (PD, Five Star, Sinistra/Greens and Azione and Italia Viva) actually came to a total of 49% against the right-wing’s 44% in the Camera, and there was a similar result in the Senate. The problem we’re now facing was not - therefore - predominantly down to a far-right surge but the fact that the many disparate groups to the left of centre failed to put aside their differences to campaign together on a joint programme. The immediate solution to Meloni’s rule is, by extension, both simple and – apparently – very difficult to achieve. A broad coalition led by the PD and Five Star Movement, including all the smaller parties, could be - is arguably already - a winning force.

IV: The ‘party of abstention’ is the biggest bloc

37% of Italians abstained during this electoral contest. That figure, to put things in perspective, is 9% worse than the last national elections in 2018, indicating a massive increase in apathy, anger, frustration or whatever else. It’s also - let’s not forget - 11% higher, as a figure in its own right, than Meloni’s result. So if you’re sitting here worried that Italians have become “neo-fascists overnight”, or whatever, this is absolutely not the case. The majority of citizens, as shown above, support the left or centre. The bigger and growing problem, however, is that a vast, terrible, number have also given up on participating altogether.

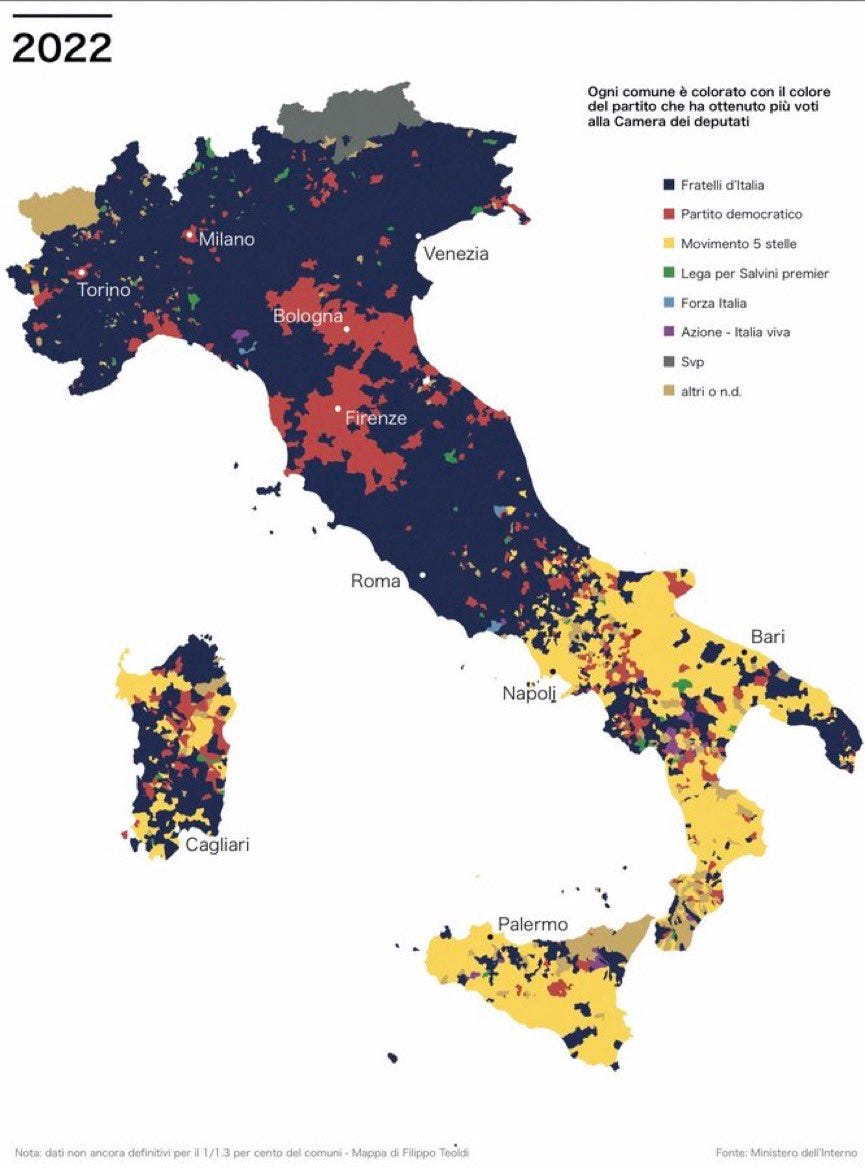

IV: The Five Star Movement remains the most influential force in Italian politics

I’m not saying I ‘endorse’ M5S but there’s no denying the movement will have to play a part in any progressive vision for Italy. One reason for this is that based on post-vote analysis they are – definitively – the party of both the young and of the south. While turnout in Sicily, Campania, Puglia, Sardinia was abysmal, these regions did, more than anywhere else, reject Georgia Meloni and the far-right. I mean, just look at the map below. Too often we think of the Italian left in terms of the old red wall of Florence, Bologna etc. In fact precarious youth, migrants, workers in Naples, Palermo, Bari are pushing for a far more innovative - if contradictory - form of progressive politics than middle class university educated intellectuals tend to recognise. M5S’s most recent programme is quite significantly more left-leaning than the PD’s; and it’s filled with commitments on economic and social justice, and pledges to tackle the climate emergency. Yes, the party is filled with opportunists who can’t be trusted. But this is true across the board. Democrats of all stripes should surely be invested in supporting M5S’s current progressive face if only to avoid it mutating (back) into a rigid, nationalistic, party-like form as per 2018. I for one think there’s something to work with here.

V: Meloni must now face the wrath of her frenemy Matteo Salvini

The Lega lost these elections big time, and the scale of that loss is important. Even in Veneto, the party’s heartland, Salvini came third - a fact which is significant for several reasons. One, the fall of the former poster boy of the populist right is a good reminder of how quickly these kinds of figures can fall out of favour (and Meloni could easily face the same fate). More importantly, though, she has immediate cause for concern. Salvini is an intemperate, aggressive, narcissistic, chauvinistic bulldog of a man. There is therefore every chance that - cornered as he is - he will detonate some kind of political bomb, perhaps by turning to the liberals to form a centrist block if it suits his interest; or simply pulling out of the still nascent government, like a playground bully, to discredit the pesky woman who stole his thunder.

VI: Aboubakar Soumahoro made it to the parliament

I admit, another valid title here might well have been “small progressive parties totally dropped the ball.” De Magistris’s Unione Popolare got 1.5%, Di Maio’s Impegno Civico got 1.2% and the (various) communists all ended up on zero-point something of a something. Sinistra Italiana and the Greens also underperformed, largely due to schisms around their - in my view - misguided opposition to sending weapons to Ukraine. Nevertheless, their 12 deputies and 4 senators will have an important role to play in pushing for economic justice. One of them, Aboubakar Soumahoro, a migrant labour leader, who is committed to advocating to protect the weakest in society via minimum wages, jobseeker benefits and introducing new rules to simplify the citizenship, residency and asylum applications is a genuine breath of fresh air for the parliament. Aboubakar struggled on the campaign trail - he got his seat by proportional vote rather than a clear cut win - but he’ll be in the Camera nevertheless and his capacity to represent the genuinely disenfranchised is a victory worth celebrating.

VII: Elly Schlein, ‘Italy’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’, is well-placed to take over the PD

This is highly speculative of course. And while I personally have limited faith in the PD elite actually choosing a leader outside of the usual technocratic bubble there is a surprising buzz behind Elly Schlein, the young, Swiss American citizen, who left the party due to its neoliberal turn but still works within its independent, related, electoral list. Enrico Letta, the current PD Secretary, has already announced that he is stepping down and Schlein - who I prosthelytize on a regular basis - is among those tipped to replace him. There are many unknowns here. It could be she never gets to the leadership; it could be she does and is hopeless; it could be she turns out to be a mere radical chic media icon with no real popularity. Or – who knows – she might just reinvent the PD and help lead the left to a swift victory over Meloni and co. There are a lot of ‘coulds’ here. But given all the factors in play – not least the probable collapse of Meloni’s coalition sometime over the next year – the PD’s choice of its future Secretary is going to be an important part of the jigsaw going ahead.

VIII: Genova shows a viable route forwards for the left

Liguria, once a heartland of socialism, has been getting bluer and bluer for years now and - in keeping with that trend - the region gave relatively strong support to Giorgia Meloni on Sunday. One of the exceptions, however, was Genova, the capital, where the PD won the local race with 26% (and small progressive parties also did well). It’s also striking that in contrast to the left-wing heartlands Tuscany and Emilia, where success is all-but guaranteed, in Genova the PD actually campaigned in poor neighbourhoods, putting real resources, time and energy into reaching people via unions, civic groups, local activists and so on. And it worked! (Who’d have guessed eh?). Still, the implications are vital. IF the PD can regroup behind a figure like Elly Schlein, IF it can coordinate a real alliance with M5S, and IF it continues to harness the grassroots through on-the-ground campaigning there’s every reason to believe a broad progressive coalition can soon outflank the country’s inept far-right populists who have so little to offer beyond ‘anti-woke’ culture war polemics.

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m an author, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. No worries if you can’t chip-in or don’t feel like doing so, but please do consider forwarding this to a friend or two. It’s a big help!