On Tuesday morning Georgia Meloni gave her first major speech as Prime Minister. Leaving aside the fact the contents were almost entirely hot air she seems to have convinced many commentators that she is, in fact, a capable and moderate statesperson. There’s no denying Meloni did an effective job of distancing herself from fascist nostalgia. Mussolini’s racial laws, she flourished, were “the worst moment in Italian history” and “as a conservative,” she insisted, she was committed to democracy and “fighting every kind of racism.” This was textbook stuff, and well-executed. More surprisingly, however, she also reiterated, on several occasions, her commitment to the EU, insisting that her wish was not “to slow down or sabotage” transnational cooperation but to “steer the institutions to be more efficient…closer to people and businesses.” Several Brussels-based commentators seem to have fallen for the moderate reformist persona, pointing, for example, to the facts that Giancarlo Giorgetti (who served as economic development minister under Draghi) will stay in his post, and that Roberto Cingolani (the ex-energy minister) will also have a formal advisory role as evidence that she will be a continuity candidate. On closer inspection, however, Meloni’s ultra-conservative agenda is more than apparent. Giuseppe Valditara, who published a discredited book claiming the Roman Empire collapsed due to immigration, will take the role of Education “and Merit” minister; Eugenia Maria Roccella, a pro-life activist, will take on a new role of Minister for “Family, Natality and Equal Opportunities”; and Francesco Lollobrigida will lead a new Ministry of Agriculture and “Food Sovereignty.” So please ignore the “centre-right” posturing and amnesiac hot-takes — as philosopher Lorenzo Marsili aptly diagnosed just after the election: “gone may be the days when the victory of far-right populists and extremists appeared unthinkable or untenable. We may instead be in a new degenerated, rightwing normality: where that honourable and necessary space in a democracy becomes perverted and consistently occupied by Trumps and Melonis.”

While much of Italy - and the world - seems to be in a “wait and see” mood vis-a-vis Meloni, not all are content with sitting still. In Bologna last week 30,000 activists with the Rise Up 4 Climate Justice movement congregated outside the city to block an ENI petrol station, and the nearby highway, in an effort to keep planetary extinction in the media. The local government, which is still run by the centre left PD, voiced support for the demonstrators insisting that, in opposition, they will push for serious action on environmental issues. Elsewhere, however, clashes have been dramatic. On Tuesday afternoon, to take just one example, a group of students at La Sapienza University in Rome congregated to protest the presence of Daniele Capezzone, a neoliberal journalist, and Fabio Roscani, a Fratelli d’Italia politician, on campus. This was a peaceful demo which, far from “no platforming” the speakers, sought to offer a discursive, if spirited, opposition to their arguments. Despite this democratic rationale, however, the police charged at the protesters - continuously - for half an hour, beating many of the protagonists in a horrific, thug-like display of brutality. Thankfully, “only” four were wounded and one arrested; though the students are, rightly, indignant and the opposition is now growing around a new and more militant call: “fuori gli sbirri dalle università” [cops off campus]. More on this as the story develops…

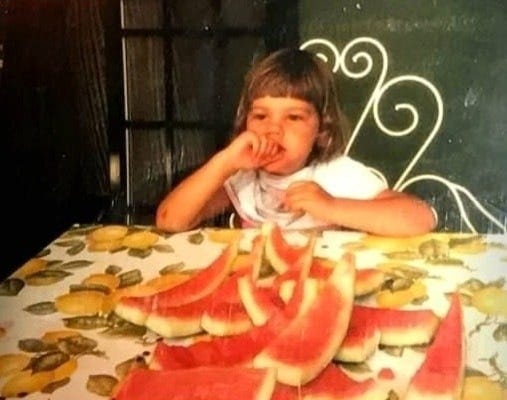

Long-time readers of this newsletter may remember the Facebook page “Pictures from Italian Profiles” which I’m particularly fond of. If you don’t, here’s a quick re-cap: Stefano Frosini, a 29 year old teacher from Pistoia, set this page up a few years ago to foreground real scenes from suburban and small town Italy as a counterpoint to the usual Dolce Vita picture-postcard stereotypes that so often dominate visual semiotics of the “bel paese”. Well, this week I was amazed to see that The New Yorker actually published a feature about the page; and not only that it happens to be a great essay that’s absolutely worth reading! The author Max Norman approaches PFIP from the detached vantage point of a smart, but engaged, critical ethnographer. He captures, for example, the “wit, the gentle pathos, and the stranger-than-fiction unexpectedness” of Frosini’s work, he notes recurrent themes like the “contrast of old age and youth”, and he correctly identifies the deep desire “to satirize and complicate any national myths: rather than reinforcing them.” His words on the medium itself are some of the finest in the piece, and I think cut right to the appeal of the page: “although Frosini’s project was made possible by social media” the author reflects, “it is not quite of it.” Brilliant, succinct and profound, read the full piece here.

Arts and culture: ‘reversing the gaze’

Igiaba Scego, the novelist, is one of Italy’s best and sadly under-appreciated writers. Born in Rome in 1970, author of twenty books of fiction and non-fiction, this Italo-Somali polymath is prolific; comfortable working in prose and verse alike while also penning journalism for newspapers and magazines like La Repubblica, Il Manifesto and Internazionale. Now - finally - English-speaking audiences have got the opportunity to discover one of her most arresting recent books: The Color Line, which was published in Italian in 2020, tells the story of two black women - an African-American woman artist living in 19th Century Italy and an African-Italian curator living in 2019– as they navigate the boundaries between past and present, art and politics, representation and creativity. It’s a formally brilliant, polyphonic, avant-garde work that, for obvious reasons, is vital political reading under the current government. One hopes, if nothing else, that it will do better in English than Italian. So here’s a link to the new edition published by Other Press, and if you’re unfamiliar with Scego, and want an intro, I highly recommend this lecture she gave in English, many moons ago at new York University, as a starting point. Trust me, this video is well worth an hour of your time. Enjoy.

Earlier this week, after six years of renovation works, Rome’s Museo delle Civiltà is (re)opening its doors. The museum, which is really a merging of several collections of prehistoric and folk artefacts, high medieval art, ‘Eastern’ art and ‘African paleontology’ has long been the object of controversy. Leaving aside the basic difficulty of presenting some of these artefacts together in the first place – even through a decolonizing lens – there are issues here to do with ownership and framing that seem hard to reconcile. Many of these objects, for example, were plundered, stolen or accumulated thanks to imperial violence, and it is surely reasonable - by extension - to ask if they should not, in fact, be returned to their places of origin. Similarly, while the rationalist buildings of the EUR neighbourhood are no doubt beautiful it would be hard to downplay the risk that housing the objects here could, nevertheless, be seen as celebration of the fascist past. The new Director, Andrea Viliani, is a prominent liberal commentator and I’ve no doubt his efforts to establish a new pluralistic and democratic curatorial practice are sincere. This piece from 2020, by Art Newspaper, however, is a sobering reminder of how quickly such a mission can nevertheless end up reproducing racist narratives. Two years since publication, the essay is more relevant than ever.

Recipe of the week: Stuffed sole in saffron sauce

This is an excellent and elegant recipe from one of my favourite cookbooks, Anna Del Conte’s The Classic Food of Northern Italy (1995). Easy enough to prep, but impressive enough to serve to guests as part of a seafood banquet, it also has a good story behind it. This Venetian dish goes back to the 13th or 14th Century as far as I know, when trade between the maritime republic and the Byzantine empire was thriving. The seasoning - saffron but also pine nuts and raisins - are obviously more typical of what we’d now call Turkish cooking than ‘Italian food’ and I find it interesting, as in the case of similar Sicilian dishes, that the exchange of ingredients and culinary legacies is so visible to this day despite centuries of war and fluctuating borders. In her instructions Del Conte insists on the importance of using good quality saffron. “[The spice] can add a deliciously complex and exotic [sic] flavor to a dish” she writes, “but it can also ruin it if used with too generous a hand.” This is certainly true. My own far less illustrious recommendation would be to serve the fish with some roasted balsamic radicchio on the side, for a really authentic taste of the region. It’s a delicious combination and the sweet and bitter flavours really play off one another nicely. Here’s the link if you fancy giving it a go.

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m an author, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. No worries if you can’t chip-in or don’t feel like doing so, but please do consider forwarding this to a friend or two. It’s a big help!