First things first: a quick roundup of the local elections, which took place over the weekend. The results – if you haven’t seen yet – were hardly groundbreaking, with no political force emerging to the foreground and the fundamental polarisation of the country once again confirmed. The centre left consolidated their lead in Parma as well as taking back conservative Verona, Padova and Taranto. The centre right, meanwhile, held on to Genova, and, I’m very sorry to report, also conquered Palermo (thereby ending decades of independent rule in the Sicilian capital… urgh). Across the country, in smaller comuni, the picture was similar with the centre left winning around 51% versus Meloni and co on 49%. One thing that is important to note is the (low) turnout. Only 54% of eligible voters turned up to the polls last Sunday (a decrease of 5% since the previous contest). And the ‘justice referendum’, which I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, was even worse. In the end just 20% of Italians voted in what Matteo Salvini had been tirelessly branding “a historic occasion for people power” in the run-up. In fact, not only did the result fail to reach quorum, it was officially the poorest and least attended such exercise of direct democracy in the history of the republic. So make of that what you will….

The question of civil liberties has been somewhat under-discussed this year, but I think a couple of stories on the topic certainly deserve more attention. Take the right to protest. Regular readers may recall that over the past few months high school students have been mobilising to oppose mandatory internships which effectively force young people into non-remunerated labour. Well, on 18 February in Turin, during one such demonstration, a group of eleven students were arrested for hitting police officers with wooden sticks and trying to force entry to a building owned by the national chamber of commerce. What happened next was shocking. Two of the kids were kept in jail for five days (because the staff couldn’t find electronic tags to send them home) and one was made to share a cell with a convicted murderer. The others were placed immediately under house arrest, where, months on, to this day, they are still forbidden from making contact with anyone beyond their immediate families. Many, such as the parent-led organisation “mamme in piazza per la libertà di dissenso”, have argued that the police response was disproportionate, unnecessarily severe, and at odds with the constitutional right to democratic resistance. And I have to say, personally, looking back at the images from that day - of cracked skulls, and teenagers covered in blood - I think it would be hard to disagree with them…

A few days ago Atlantia, the private company that has been managing Italy’s autostrade for decades, sold its shares in the national motorways to the Italian state. Now, I know this might sound small-fry; but the implications are actually “quietly historic”. Because this isn’t just a sale. The very fact the state agreed to these terms is, in itself, a modest refutation of thirty years of privatisation. And neither is this an isolated case. Talks are currently underway for the government to form a new public body to manage telecoms; and I’m told by friends close to Palazzo Chigi that legislation is also being drafted to block foreign companies from investing in national logistics too. Call this protectionist, socialist, sovereignist, whatever you want. But there’s no denying this government seems willing to take major infrastructure back into public hands in a way that was never true under Berlusconi or Renzi. If you read Italian, this piece by Antonello Salerno for L’essenziale is a good starting point for understanding the broader implications of this unexpected economic development. There will be more of this to come, I’m sure.

Arts and culture: a trip down memory lane

Giorgio Ghiglione published a truly wonderful piece for the Guardian this week about the now almost-extinct genre of Italian dance music known as liscio. Liscio, for those unfamiliar with the term, emerged in the early 20th Century as a genre of working class music in the old “red regions” of Emilia Romagna and Tuscany. The music was, and is, performed by small orchestras who play a mix of waltz, polka and tango in tiny countryside clubs until the early hours. It was once the most anticipated moment of the weekly routine for a certain portion of older Italians. Here, Ghiglione lovingly tells the story of this phenomenon, from its origins in industrial, provincial villages to its decline during the metropolitan heydays of punk and disco, and ultimately, the final nail in the coffin, the Covid restrictions, and the virus itself, which are destroying what’s left of the scene. If you’ve never heard of liscio, the track below, by Raoul Casadei, gives a good sense of the genre. If you have, then Ghiglione’s piece is a must read. So here’s the link.

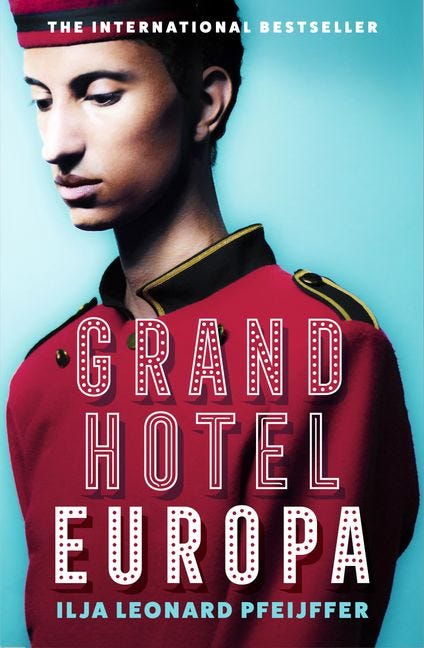

Speaking of nostalgia: I wonder, have you ever found yourself sucked into a reactionary fantasy of Italy? Ever had the sinking sense that everything good in this country, as in Europe, belongs to the past? That the present and future are nothing but an inexorable, inevitable decline? Well, if the answer to any of the above is “yes” then you may want to check out Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer’s latest novel Grand Hotel Europa. Set in an unnamed Italian city, in a faded pensione, the book describes a man’s attempt to recover his self esteem after a failed love affair. The setting is functional - OK - but it also works to provide a broader lens through which the narrator can reflect on the realities of contemporary Italy: the alienating impact of mass tourism, the seductive nature of nostalgia, and the enduring beauty of old art among other things. One reviewer in the NYT recently described Pfeijffer’s style as “calling to mind Nabokov, Tom Wolfe, Baudrillard, Umberto Eco, Wes Anderson and a UNESCO position paper.” So, if that kind of thing is up your street – and I know it is mine – this might well be one to add to your summer reading list.

Recipe of the week: Cod, lemon, olive and chili salad

Finding a summer salad without tomatoes in Italy can be a tricky business. From panzanella to caprese to condiggion, almost all the “traditional” June-September dishes seem to make use of the nation’s most prized vegetal product. Now, loving tomatoes as I do, this is no great cross to bear. But sometimes, I admit, one wants a little break. On such occasions, if you ask me, cod and lemon salad is just the job. And it couldn’t be simpler. Simply boil up the fish, mix with lemon juice and oil, then stir through olives, chili, garlic and parsley. Done. I add some chickpeas, and serve with bread, to eek things out; but feel free to improvise as you see fit. The only thing I would emphasise is the importance of using a) a good quality olive oil and b) plenty of lemon juice. I, for example, use Gennaro Contaldo’s recipe but triple the dose of citrus: something I can highly recommend for any readers that enjoy a refreshing, sour hit when the temperatures start to soar.

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m an author, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. No worries if you can’t chip-in or don’t feel like doing so, but please do consider forwarding this to a friend or two. It’s a big help!