Europe or Trump? Decision time for Giorgia Meloni

Plus, a feminist manifesto and proto-renaissance art from Siena

It seems like Italy has been talking about one thing and one thing only this week: President Trump’s suspension of military aid to Ukraine, and the implications for the West and the world more generally. This isn’t the place for grand analysis (I’ll leave that to Timothy Garton Ash). Instead, what I want to focus on here is the more modest question of how Giorgia Meloni has been navigating the issue. Frankly, the Italian PM is in a tight spot. On the one hand, she’s been trying to reassure EU allies that she’s a sensible conservative who has the continent’s best interests at heart. At same time, she has openly courted Trump and has repeatedly endorsed some of his more extreme views. This week, as tensions between the U.S. and EU escalated, the Italian Prime Minister was, in theory, forced to take a position. Once again, however, she kicked the ball down the line and succeeded, to some extent, in playing both sides. On Tuesday, in a rare interview with RAI’s XXI Secolo, Meloni declared she was “for Italy, for Europe and for the West” (note all three categories). Regarding Trump’s car crash of a meeting with Zelensky, she noted merely that “such talks shouldn’t have happened on camera,” and cleverly used flattery to gaslight POTUS and undermine his own argument: “Trump is a strong leader and he clearly cannot afford to sign an agreement that someone could violate tomorrow.” She ruled out Italy sending troops to Ukraine, thereby distancing herself from Britain and France, yet seemed to hold the EU line on the question of tariffs (albeit with space for manoeuvre): “on tariffs, I disagree with Trump. I don’t even think a trade war is convenient for the United States, but there may be different points of view.” So, what to make of all this? Meloni delivered her lines confidently, as if she was clarifying her position to the world. In the end, though, her performance seemed to me like yet another act of mystification: impressive rhetorically but almost entirely devoid of substance. At this point one really has to wonder: how long can she keep this up? And which side will she really (be forced to) take as the EU and the U.S. drift further and further apart? Check out the full ITA interview below, and for more ENG analysis head over to Euractiv.

Have you ever heard of Isola Sacra? Chances are not, I’d imagine. There’s no particular reason you should have. This week, however, the journalist Giorgio Ghiglione published an excellent piece about this small inconspicuous port just twenty minutes from Rome on the Lazio coastline which, as he demonstrates, offers a good snapshot of the economic interests at work in Italy today. In his report, Ghiglione outlines controversial plans to transform this small community – little more than a fishing village – into a gargantuan, industrial cruise port. The purpose of the investment (which is funded by Royal Caribbean and the British building firm Icon Infrastructure), is to connect Fiumicino airport more effectively with the Mediterranean Sea, and to provide cruise tourists with a more “comfortable” alternative to the port at Civitavecchia. The local municipality supports the endeavour on the basis that it will bring jobs to the area. Meanwhile, many residents, and fishermen in particular, are furious. Cruise ships, as is well known, create serious environmental havoc; they upset marine ecosystems, pollute waters and dramatically transform local cultures. In this instance, the proposed project will involve paving up kilometres of coast with concrete, something that would clearly be a disaster for the local population and for the landscape. To find out more, including prospects for resisting, click here.

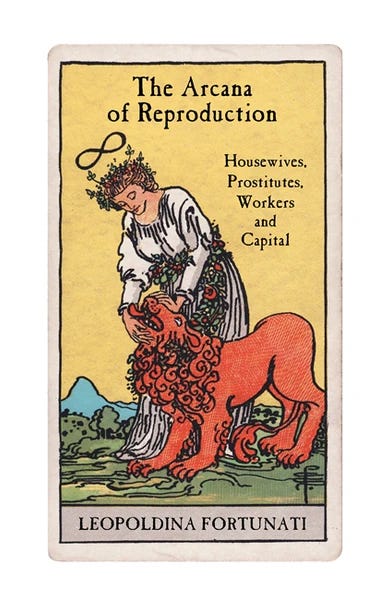

My colleagues over at Verso Books have just published a new Italian title that may be of interest to some of you reading. The Arcana of Reproduction: Housewives, Prostitutes, Workers and Capital (trans. Arlen Austin, Sara Colantuono) is a landmark work of theory by the feminist philosopher and sociologist Leopoldina Fortunati that has had a deep impact on Italian activism over the past few decades. First published in 1981, during the birth pangs of neoliberalism, and at the very moment that Silvio Berlusconi was rising the ranks of the entrepreneurial class, the author offers a key criticism of the capitalist economy, outlining some revolutionary reflections on ‘care work as work’ as well as ‘immaterial’ and ‘affective’ labour. Fortunati was, together with Silvia Federici, one of the key figures who fought to ensure that women’s’ perspectives, subjectivities and experiences were properly integrated into Marxist and other progressive frameworks, and that’s reason enough to take this seriously in my book. But at a moment when women’s’ already limited rights are being stripped back so savagely, this re-release feels particularly timely. So read an extract over at e-flux and buy a copy straight from Verso.

Arts & Culture: Tuscany’s proto-Renaissance

One of the best places to see Italian art this week is not in fact in the bel paese at all, but in the UK. This weekend, the doors of London’s National Gallery will open on a landmark exhibition dedicated entirely to the still criminally under-appreciated works of medieval art that were produced in Tuscany in the years immediately preceding the renaissance. Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350 is a bold effort to valorise the contribution that artists such as Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini made to the history of visual culture in Europe. Following a 2024 stint at the Met, this new show emphasises the intimacy and sensitivity of the Sienese art of the period; counterposing the esoteric, deeply personal works of veneration with the homogenized cultural products of our own time. Obviously, as a Tuscan resident, living one hour from Siena, I’ve had my fair fill of all this stuff over the years, but it’s always gratifying to see these works getting international attention. To quote Jackie Wullschläger in the Financial Times review: “this exhibition will be one of the year’s wonders.” For further reading about these painters’ works, and a personal meditation on their contemporary relevance, I’d also recommend Hisham Matar’s 2019 memoir A Month in Siena.

After much-hype and an interminable wait, Netflix’s new small screen adaptation of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s classic historic novel The Leopard has finally arrived to generally favourable reviews. My verdict? This is fine TV. I admit, I was sceptical. Luchino Visconti’s 1963 film is one of my favourite movies of all time and when I heard Netflix was having a go, I found the prospect almost sacrilegious. In the end, while the result is flawed, it does fulfil a certain purpose. The plot is intact, the acting is strong and it all looks gorgeous. What’s missing, however, is nuance. I’m struck, for example, by the fact that some critics are celebrating this as a “look at how the ruling classes survive social upheaval.” The reality, of course, is the opposite. Garibalidi’s revolution did after all destabilize the old nobility; and the rise of the bourgeoisie did end of the hegemony of the Bourbon elite. Don Fabrizio’s ludicrous efforts to deny this, and his mediterranean gothic fixation on death and decay, are the metaphorical lifeblood of di Lampedusa’s novel, and Visconti captures that masterfully. This Netflix show does not. So please forgive me a moment of pomposity: while it may be good looking, this series is a mere simulacrum of the source material.

Recipe of the week: Sicilian chicken with couscous and lemon

Sticking with Sicily, this week’s recipe is a non-traditional dish by Francine Segan which she published over at Italy Magazine last year and which will absolutely fit the bill given the balmy spring weather we’ve been enjoying these past few days. The recipe boasts a long, spice-heavy ingredient list of the kind that’s typical of the island’s medieval cooking (though the use of poultry is, for sure, a modern preparation). Saffron, cinnamon, cardamom, nutmeg, all-spice and cloves all make an appearance, as do dried fruit and nuts. What first drew me to this dish, however, was not so much the Arab flavouring but the imperative to cook the meat using “the brick trick”, i.e. charring the chicken skin by weighing the cuts down in the pan with a heavy object of some kind. Trust me, follow the instructions to the letter and you’ll be guaranteed crispy, smoky meat with a soft, juicy middle. Truly a delicious topping for couscous! This one’s behind a paywall I’m afraid, but if you don’t subscribe to Italy Magazine and you’d like to cook this you can sign up for a free 30-day trial. So here’s the link.

I’m Jamie Mackay, a UK-born, Italy-based writer, working at the interfaces of journalism, criticism, poetry, fiction, philosophy, travelogue and cultural-history. I set up ‘The Week in Italy’ to make a space to share a regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds, to explore politics, current affairs, books, arts and food. If you’re a regular reader, and you enjoy these updates, I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month. I like to think of it as a weekly catch-up chat over an espresso. Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. Grazie!