Mario Draghi sounds the alarm

Plus, a history of "ruin tourism" and a new Alba De Céspedes translation

Former ECB president and ex Italian PM Mario Draghi made headlines across Europe this week with a dramatic intervention regarding the future of the continent. On Monday, during an address to the European Parliament, Draghi spoke about the existential challenges the EU is facing — from democratic decline to economic slowdown — renewing his call for greater centralized investment in a number of “strategic” sectors. In today’s world, he said, Europe needs to be “united” and “faster […] speed, scale and intensity will be essential.” To most of us, these words may sound reasonable, even banal. In the context of the rise of Trumpian sovereignism, however, Draghi’s statement was a political provocation. What he was really saying, amidst all the euphemism, is that the EU needs to work more like a single state in order to withstand the impact of upcoming U.S. trade tariffs. As things stand, he argued, Europe is wasting too much time due to the ambiguous division of competencies between nation-states, regions, and the EU institutions like the Parliament and Commission. Instead of fretting, the ECB and other actors should immediately embark on a coordinated and unified investment programme of 800 billion Euros per year to catch up in high-tech sectors, the green transition and defence, in order to boost the EU’s “competitiveness”. In some respects, these are the same arguments Draghi presented in a high-profile report last autumn, which received a mixed reception across the continent. Now, however, his argument is even more urgent. With Trump moving fast in his foreign and economic policy, there is a growing sense that the EU is already on a new path: either it will be reshaped by Elon Musk’s radical de-regulation agenda or it will make its own way (something policy wonks call “strategic autonomy”). While few would disagree with Draghi’s assessment, the real questions now regard practicalities: who should fund Europe’s renewal? How should they do it, and how quickly? Or, as Draghi himself put it in a final provocation: is it time for common EU debt? Guillaume Duval has penned an excellent analysis for Social Europe that’s pleasantly free of jargon, so check it out here if you’re interested in the nitty-gritty details.

If you’ve been following recent debates in the Italian parliament, you may already know that at the end of last year the government signed a bill to introduce new measures to address crime and poverty in the country’s most deprived suburbs. The so-called “modello Caivano” (named after a district to the north of Naples) outlines one leading strategy to achieve this. While there are some perfectly reasonable measures here (like “funding education”), far too many of the proposals are punitive and involve deploying more police, multipling “red zones”, and ensuring “greater state presence” in seven neighbourhoods: Rozzano (Milano), Alessandrino-Quarticciolo (Roma), Scampia-Secondigliano (Napoli), Orta Nova (Foggia), Rosarno-San Ferdinando (Reggio Calabria), San Cristoforo (Catania) and Borgo Nuovo (Palermo). As the list grows, however, so too does the backlash. This week, NGOs and civil society groups in Quarticciolo outlined their vision of, and argument for, a bottom-up model of development. At the core of their alternative vision are measures such as reopening cultural and sports centres, improving addiction clinics, investing in better healthcare and creating jobs together with existing enterprises, in order to bolster employment and civic pride. There are hundreds of pieces out there on this subject, but I want to flag-up this essay by Mario Pinceta for Jacobin ITA and this by Annaflavia Merluzzi over at Il Manifesto which both offer an intelligent and in-depth look at what Quarticciolo tells us about Italy today.

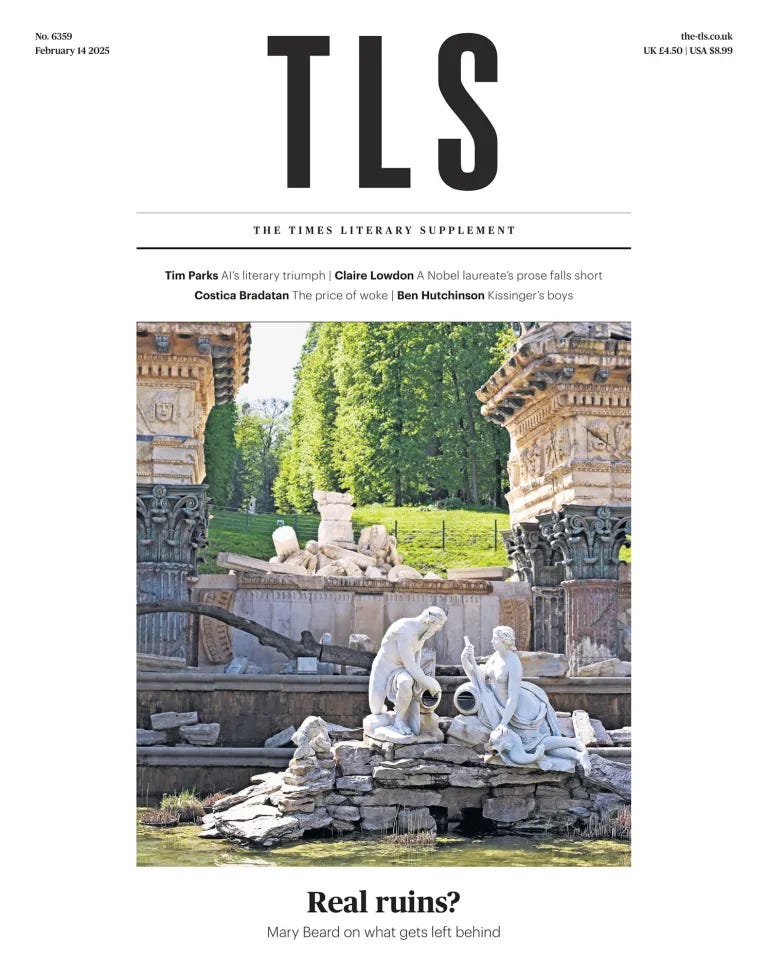

The historian and classicist Roland Mayer has got a new book out about the changing topography of the Italian capital from its foundation until the present day which is sure to interest any readers interested in ancient archaeology. The Ruins of Rome: A Cultural History brings together testimonies from travellers, poets, artists and philosophers in order to chart “the changing attitudes towards the monuments of ancient Rome and the emotional, aesthetic and intellectual responses to the city of Rome's ruins over the past two millennia.” Starting with a fascinating inquiry into whether and to what extent the ancient city’s inhabitants were inspired (or not) by the ruins they found around them, Mayer takes the reader through medieval chronicles (when, he argues, nostalgia began) through to the Grand Tour, when Romantic myth took centre stage, right up to fascist era propaganda and, finally, our own digital age in which virtual models and reconstructions are redefining the social meaning of ancient sites. This is a fascinating, if rather dense, study, targeted at experts in the cultural sectors. So for a breezier overview, and a taster of the contents, I recommend first checking out Mary Beard’s review for The Times Literary Supplement here.

Arts & Culture: War-torn Fragments

Another book for you now — this time a new translated fiction title. On 13 February, Pushkin Press/Washington Square Press released an ENG edition of the Italian-Cuban author Alba De Céspedes’s anti-fascist novel There’s No Turning Back (1941). The book, rendered into English by the inestimable Ann Goldstein, traces the lives of eight young women living in a convent-boarding house in Rome during the mid 1930s. There is no plot exactly. Instead, the narrator flits anxiously between the viewpoints of these women, all of whom come from dramatically different backgrounds, in order to detail the subtle ways in which they each reject fascist gender norms. Interestingly, Céspedes makes no explicit reference to Mussolini or to the regime. Instead, she relies on allusion, anecdote and idiosyncratic subversion to unravel the dogmas and ideology of the time. The result? A powerful celebration of human freedom, desire and dignity over authoritarian oppression. Check out this fine essay by Goldstein, over at Lit Hub to find out more (and while you’re at it you might also want to bookmark Céspedes’s Forbidden Notebook, also translated by Goldstein, which was released in 2023).

The singer-songwriter, producer and multi-instrumentalist Jacopo Incani (better known by his alias iosonouncane) is rapidly establishing himself as one of Italy’s preeminent millennial composers of film music. This week, on the back of the success of ‘Gli ultimi giorni dell'umanità’ and ‘Berlinguer - La grande ambizione’, the musician is releasing a new score, this time to accompany a documentary called Lirica Ucraina which, as the title suggests, explores the frontlines of the war in Ukraine. Incani single handedly composed, produced, recorded and arranged all of the parts on this record, mixing classical piano and experimental electronica with simple synth textures and gentle percussion. His intention, as he’s stated in numerous interviews now was not just to provide a “background to the narrative events of the film” but, inspired by composters such as Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross, “to amplify the lyrical power of the images and reinforce the director's gaze.” Find out more about the film here, and listen to the full album on Spotify from midnight on 21 February.

Recipe of the week: Red cabbage risotto w/ parmesan fondue

This week’s recipe is a real feast for the eyes: a dramatic, striking risotto, boldly tinged with purple brassica, but rich, creamy and nourishing enough for these cold winter days we’ve been having. Mario Antonio Cioffi published this recipe towards the end of last year in the November edition of La Cucina Italiana but I only just got round to making it — and I have to say, it was lovely! The technique here is fairly straightforward. This is a classic risotto without any funny business. You will, however, need to set aside a good few hours for boiling the vegetables to make a stock and for preparing the ‘cabbage cream’ (which you blitz and then add half way though cooking, in case you were wondering). None of this is particularly taxing, but the results are impressive, elegant, tasty and certainly hearty enough to whip-up for a crowd. Serve in small portions with a green salad and a glass of pinot nero for a full gourmet experience. Here’s the link [ITA only I’m afraid, though Marcella Hazan has an equally good, if meatier, ENG version here if you’re interested.]

I’m Jamie Mackay, a UK-born, Italy-based writer, working at the interfaces of journalism, criticism, poetry, fiction, philosophy, travelogue and cultural-history. I set up ‘The Week in Italy’ to make a space to share a regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds, to explore politics, current affairs, books, arts and food. If you’re a regular reader, and you enjoy these updates, I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month. I like to think of it as a weekly catch-up chat over an espresso. Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. Grazie!