Earlier this week a rather shocking event took place which would have been dreadful enough at the best of times but which in the midst of this pandemic obtained additional grim significance. On Monday, a large portion of the Cemetery in Camogli, a town to the south of Genoa, collapsed into the sea, with the result that 200 coffins were left floating in the Ligurian riviera. This is a rather morbid image to start off this week’s newsletter, I know. But for Italians, and Ligurians in particular, the event did seem to capture a lot of things: the importance of respecting the dead, the vulnerability of the many thousands that are currently in mourning, the general sense of economic and social decline. Coming on the back of the Morandi Bridge disaster, though, which killed 43 and left 600 homeless in Genoa just three years ago, the scenes in Camogli also served, more specifically, as a smaller-scale reminder of the negligence of the regional administration. In recent months some particularly apocalyptic-minded individuals within the clergy have been searching for signs that God is unhappy with the world (see below for a particularly colourful example). I’m not a Catholic, but I do think this incident has a symbolic dimension. Italians often talk about government as being not only corrupt but as holding actively malevolent intentions towards the population. When events like this happen, which are so easily avoidable, and which involve such sensitive matters, it’s easy to see why anti-political sentiment is so widespread here.

I’ve always had an aversion to political gossip. Still, for anyone trying to get a handle on what the new PM Mario Draghi is like as a person (or at the very least grasp a quick overview of his bio), this podcast from Politico Europe is quite entertaining and informative enough. Based on the discussion he comes across as a serious man; well-trained in the art of gentillesse if fairly rigid in his vision of European integration. I also learned he is a Jesuit which I didn’t know before listening. Another thing that jumped out at me here was one of the guests’ definition of the new government as representing a kind of ‘technocratic populism’. What a mouthful! As many readers will know analysts have long pointed to Italy as a kind of ‘laboratory’, where politics is both ‘behind’ yet simultaneously ‘ahead’ of the curve. Think, for example, of the 1970s, and how the demands of the Italian labour movement helped shape Europe’s freelance economy (for better and worse); or how Berlusconi’s leadership style provided a template for Trump and Johnson; or simply the fact that Italy, which has a notoriously low internet penetration rate, has propelled Europe’s first ‘digital democratic party’, the Five Star Movement, into government. Mario Draghi, a Central banker, currently enjoys the support of everyone from the far-right leader, Matteo Salvini, to Mario Tronti, the autonomist Marxist theorist. It’s a peculiar state of affairs, and it does beg the somewhat superstitious question: is this what the capitalist recovery will come to look like elsewhere? Or is Italy just an anomaly?

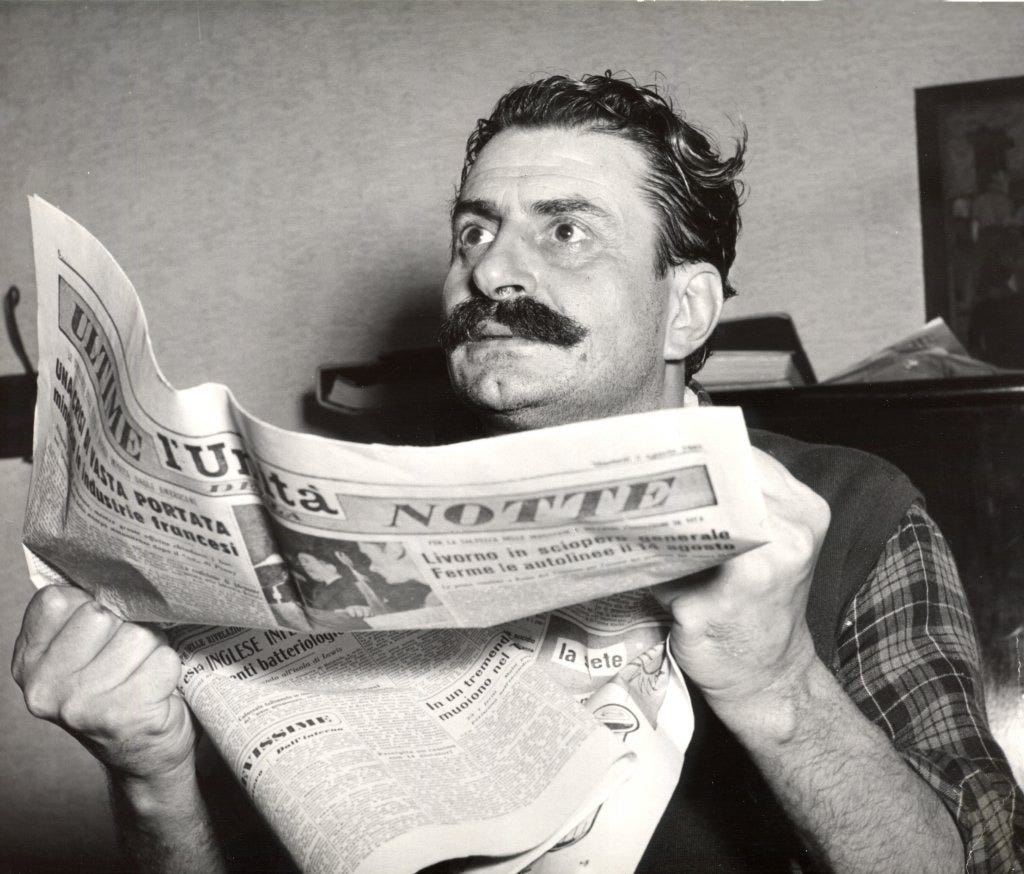

Flicking through the usual newsfeeds this week I was reminded again and again what a great journalist Tobias Jones is. If you don’t know Jones’s writing, his books The Dark Heart of Italy (2003) and Ultra (2019) are good places to start. He’s clearly been busy of late. I enjoyed his Guardian piece about the socio-economic consequences of Covid in Italy, which chime with my own observations. I also noticed, though, that Jones has just published a more off piste essay about Giovannino Guareschi, ‘The Italian Orwell’ on a peculiar website called Engelsberg Ideas. It’s a very interesting profile of an author I imagine very few readers will be aware of. I for one am now inspired to hunt down some of those Don Camillo satires... incidentally, on a side note, while searching for further info about the author on twitter I also noticed Jones posted this rather wonderful historical nugget about ‘medieval monopoly’; a dice game from Bologna which was invented sometime around 1691. This has nothing to do with the news, admittedly, or Guareschi for that matter, but there’s an image of the board on creative commons, via the British Museum website, so I thought I’d post it here.

This week I’ve been sinking my teeth into what is probably the most important Italy-related non-fiction release of 2021: Ciao Ousmane: The Hidden Exploitation of Italy's Migrant Workers by Hsiao-Hung Pai (Hurst: 2021). This is an ethnographic study, which looks at the way poor and largely undocumented workers, many of whom are African in origin, are navigating life here. Hsiao-Hung Pai is a formidable researcher, and, for UK readers in particular, her book Chinese Whispers: The Story Behind Britain's Hidden Army of Labour (Penguin: 2008), is another must read. Here she looks, among other things, at the lived experience of colonial legacies, racism and abusive labour practices in the agricultural sector. I plan to review this in full for my Polish column at Krytyka Polityczna soon (which I realise I haven’t mentioned before here, given that, well, it’s only available in Polish for now.) My recent pieces have explored sexism on Italian TV, and the limitations of the ongoing ndrangheta trial. If you’d like to read either one in English, or any future columns, then do let me know and I’ll see if I can make something happen.

Arts and culture: portraits of ‘the old normal’

This February the photographer Niccolò Berretta released a book called Stazione Termini, Lookbook 2009-2021, which gathers together images he has taken in Rome’s Central Station over the past decade. Termini, if you don’t know it, is a wonderful, but pretty chaotic space. It’s huge and dirty, surrounded by fast food joints and odd shops. It’s like any big European station, basically, yet somehow just more. Berretta’s work, which I first encountered in an exhibition a few years ago, gives a great taste of what it’s like to spend a long afternoon in that huge atrium waiting for an inevitably delayed train while cruising the numerous coffee bars. VICE Italy have got a piece up with some other shots from the book that is worth a scroll. I also want to take the opportunity here to flag up Termini TV, which Fran Atopos Conte set up in 2014 (I think); and which, as the name suggests, gathers video interviews with those passing through the station, in Italian, English and many other languages. I’m pleased to see Fran is still keeping things going despite the pandemic. On a personal level it’s just been nice to look back on his work and remember a time when people watching in Rome was a regular and highly enjoyable part of my life.

If you’re a fan of Elena Ferrante I highly recommend you check out this piece, by Jennifer Wilson, in The Nation which was published last week. It is, in a sense, a straightforward review of The Lying Life of Adults (Europa 2019). But it also does some more important work, I think, by foregrounding class as one of the key lenses through which to approach the author’s fiction. This might sound like stuffy essentialism (as if Marxism were the only way of reading texts). That’s not at all what Wilson is suggesting. There’s no escaping the fact, though, that Ferrante has an image problem; the covers of the Neapolitan Novels are horribly twee, and appeal to a normative, out of date, and exclusively bourgeois idea of femininity. I think that’s a shame: it’s reductive, it puts readers off, and it’s not at all reflective of the books themselves, which, among other things, offer an sharp portrait of how capital and social status serve to keep certain groups in poverty. I was, I’ll admit, lukewarm about Lying Life itself, which I reviewed in the original version for Italy Magazine last year. Wilson’s piece, though, has convinced me to give it another chance...

Recipe of the week: Minestrone alla genovese

Spring is here! So as long as the sun stays out I’m enjoying lighter, greener, healthier fare. Focaccia, or a simple herb-filled pie for lunch; soup in the evenings. You get the picture. Minestrone is a strong point of Italian cuisine, and there are countless versions. The Genoese approach, which mixes a kind of pine-nut free pesto into the broth during cooking, is my personal favourite (it’s similar to the French pistou, which people eat along the Côte d'Azur and which is also very tasty.) The main distinguishing trick in Liguria, which I do appreciate, is that they add a parmesan rind during cooking. This is a neat way of reducing kitchen waste and it adds a lovely savoury note. La Cucina Italiana’s English edition have a good enough recipe using late winter/early-spring vegetables. Frankly, though, you could do this with a bag of frozen produce and add your own home made pesto and it would still be great. The pasta, by the way, is entirely optional here. If anything, I actually recommend you ditch it as the dish works fine, perhaps even better, without it.

That’s it for this week - as ever I do hope you enjoyed this instalment. If you haven’t already, please do follow the ‘Week in Italy’ Facebook page, or my twitter, for a few extra links and easy-access to the substack archive. If this email was forwarded to you, or you’re accessing on the web and would like to receive further updates, you can subscribe using this link below. Thanks!

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m a writer, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope down the line you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Starting from the spring, all paying subscribers will have access to additional content including original features, analysis, reviews and interviews as well as flash updates about elections, breaking news, data and opinion polls.