Hi everyone, welcome back to the ‘Week in Italy’ and specifically to this new trial format where I’ll be attempting to reconcile more in-depth commentary and reporting with my usual curated news lists and cultural tips. This week’s top slot is dedicated to the rather niche topic of local elections, but don’t worry - if you’re totally fed up with party political news I’ll also be using this space in future editions to go into more detail about current affairs, cultural events, whatever strikes me as relevant and interesting on a given week. But enough with all these announcements already. Let’s get started!

The Week in Italy will always be free, but it’s only possible because of paying subscribers. Thanks, as ever, to all of you who have signed-up to support this work and independent journalism in general. I’m eternally grateful <3

For a fleeting moment it looked as if the Italian opposition parties were beginning to wake up. But alas…

On 25 February a left-wing alliance, led by the Partito Democratico (PD) and the Five Star Movement (M5S), won a surprise victory in local elections in Sardegna when their candidate Alessandra Todde was elected President of the Region.

Todde’s success caught all of the party leaders off guard, not least PM Giorgia Meloni who, for a brief moment, looked more vulnerable than she has at any point since taking office. For a few weeks the Italian media was abuzz with talk of a ‘campo largo’, a broad cooperation between the PD, M5S and other smaller parties, who, some speculated, could be capable of taking power across the country.

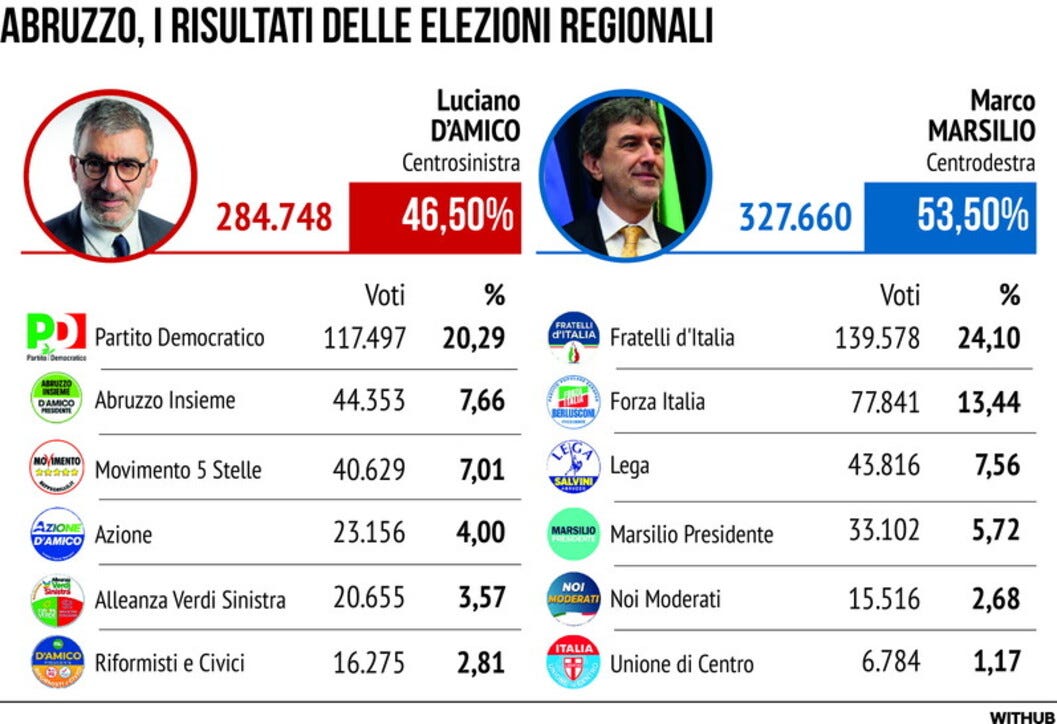

A few days ago, when first I set out to write this update, the ‘campo largo’ was gathering momentum. The mood among the opposition was optimistic. That optimism, sadly, has proved short-lived. Despite some encouraging opinion polls, the still-nascent PD-M5S alliance suffered a resounding defeat over the weekend in the poor central region of Abruzzo. Schlein and Conte had looked confident when they were touring the towns and villages of Abruzzo’s rural interior, but the final results spoke to the same well-known reality. 53.5% of voters backed the (far) right. 46.5% backed the left. Turnout? A depressing 43.93%.

Local elections are — by definition — marginal, but they do tell us something about the national mood, or at least a fraction of it. They also reveal the strengths and weaknesses of political parties, the temperament of leaders, the organisation of the grassroots, the extent of anti-political sentiment in a given territory.

In this latter sense, at least, Abruzzo is certainly instructive.

But first a word on the region itself. For those who aren’t familiar with the area, Abruzzo is a central, mountainous region, bordering Rome and Lazio. Despite its proximity to the capital it is extremely isolated due to the great peaks of Gran Sasso and the Maiella; two of the highest Apennine massifs. Abruzzo is a wild, cut-off place that, with the exception of its Adriatic coastline, defies the stereotypical image of the Italian countryside. The climate is harsh. Freezing in the winter, scorching in the summer. The hillsides are too vertiginous for growing wheat; too arid for cultivating vegetables on a large scale.

Once renowned for its sheep-farmers, Abruzzo was heavily industrialised in the 1950s and 60s. 83,9% of businesses in the region are now classified as “industrial”; more than double the average for Central-Southern Italy. Key sectors include textiles, chemicals, food processing and telecoms. With a few notable exceptions, Abruzzo’s cities are grey, grim and austere. Many of the medieval settlements have been destroyed over the years by earthquakes which are — unfortunately — common in the region. One particularly lethal quake took place in 2009, killing 300 people and leaving 66,000 homeless. The region is still struggling with the consequences.

Abruzzo is a politically promiscuous region. Over the years (and decades), voters have oscillated erratically between the left and right. “They’re all the same” is, by now, a regional mantra. That said, more immediately, and more concretely, Fratelli d’Italia has been governing here since 2019. And on paper, their administration has been unremarkable. The economy has continued to stagnate. They’ve promised infrastructure projects they haven’t delivered on’. A flagship train-line from Rome to Pescara remains incomplete. The healthcare is some of the worst in the country. Other public services are severely wanting.

Going into these elections, the left put forward a relatively strong candidate; Luciano d'Amico, a working class economist specialised in agricultural science. Born to a poor farming family, d’Amico “knows” the challenges the region is facing, and seems to have the technical-political skills to offer solutions. His speeches, during the campaign, were compelling. His arguments and policy commitments were clear and rational and included pledges to revitalize the agricultural sector, to valorize eco-tourism, to invest in schools and public spaces. Most importantly of all, d'Amico had the support of all of the main opposition parties which, in Italy today, is something of a miracle.

So why, in the end, did the (far)right triumph in these elections? And what are the implications for the opposition as a whole?

There are many possible answers, of course, but the most important, I’m afraid, concerns the frankly unsexy topic of electoral lists.

D’Amico himself was an impressive candidate. A lot of voters liked him. He ticked all the boxes as a political leader. The fatal problem, however, was that his allies — i.e. those listed alongside him — had been overwhelmingly involved in previous administrations. Indeed, over half the protagonists in the ‘campo largo’ list had previously been in office in the terrible years of post-earthquake economic crisis. Michela Carpente, Antonio Ginnetti, Emanuela Iorio, and many more. The right may have put forth a loathsome leader with a poor track record in the form of Marco Marsilio, but elsewhere in the region they offered fresh-faced candidates; less implicated in previous failures. People like Gianpaolo Lugini, to name just one. The consequences, of course, were entirely predictable. It was a wipeout.

So what, at the end of the day, can the opposition learn from this brutal defeat? And what can we, as observers, gleam from this ultimately uninspiring contest?

The lesson, I think, is a simple one.

An ad-hoc ‘campo largo’ alliance isn’t going to save the opposition in and of itself. And neither are charismatic leaders. Yes, cooperation among the major parties is a step in the right direction. But without a strategy, without messaging that can appeal to poor rural regions, without new, young candidates, untainted by the terrible centre-left policies of the austerity-era — there’s no chance. With more elections upcoming in Basilicata on 21 April, it’s time for the red-yellow alliance to take some bigger and more decisive risks, to make a more definitive and comprehensible split from the neoliberal parties of the past decade. One thing is for sure: posturing alone will not convince this highly jaded electorate.

In other news

Gabriele Di Donfrancesco has written an enlightening piece for Jacobin about the PD’s clumsy attempts to brand the influencer Chiara Ferragni as a beacon of progressive left-wing values. Read here for a deep dive into how the party has come to rely on an Instagram star as a proxy for its own social media messaging (and why that’s a terrible idea).

A few weeks ago Stanley Stewart published an interesting feature for CN Traveller about one of my favourite cities, Palermo. There are some smug asides, some fantastical untruths (“it refuses to be gentrified”), some judgements of dubious taste (“vulnerability is always so seductive”) but the tips are, generally, good and the photos by Alistair Taylor-Young make this worth a look in its own right.

Looking for a new Italy-related series? Chiara Martegiani has just released a new show on Amazon Prime called Antonia; a comedy-drama about a young woman who, on her 33rd birthday, argues with her best friend, loses her job and discovers she has endometriosis. Cineuropa has branded this series “the Italian fleabag” for better or worse — so make of that what you will.

Dario Bassolino, the Naples-born jazz pianist, producer and composer has got a new album out called Città Futura which I’ve been enjoying the past couple of days. It’s a retro 70s funk-inspired record which, while obviously backward-looking, also seeks to capture that avant-garde creativity of the era. It’s a lot of fun, so listen here.

And finally: thought I’d abandoned the recipe of the week? I still got you / looking for an excellent bottle of (natural) wine? well here you go / a classic read? ditto / oh, and if you’re in Florence right now get on down to this journalism festival

I’m Jamie Mackay, a UK-born, Italy-based writer, working at the interfaces of journalism, criticism, poetry, fiction, philosophy, travelogue and cultural-history. I set up the Week in Italy to make a space to share a regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds, to explore politics, current affairs, books, arts and food.

If you’re a regular reader, and you enjoy these updates, I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month. Think of it as a weekly catch-up chat over an espresso. Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. Grazie!