The political battle over the minimum wage has dominated headlines in Italy this week, though it remains unclear where exactly the debate is heading. If you aren’t aware Italy is in fact one of just six EU countries that has no such legislation (the others are Austria, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland and Sweden). The argument for the current system, for those who defend it, is that collective bargaining provides high pay for most workers and that this flexible, mediated approach, of so-called CCNL contracts, is a functioning part of the national labour market. The data, however, tells a different story. Italy saw the biggest decline in wages of all EU nations at the end of 2021 and purchasing power is now one of the lowest in the bloc. On Monday the European Parliament approved a directive “to set adequate minimum wages” for all EU workers who have a contract. The figure is EUR 9 per hour. Vitally, however, there’s no formal obligation to respect this ruling without a national law in place, so for now the Italian government is split on how to proceed. The PD and M5S are in favour of new legislation on the basis that a minimum wage guarantees a baseline protection for all salaried workers. The right wing parties oppose it, claiming the measure would do little to help the precarious poor and could potentially make wealthier workers, in some sectors, worse off. Obviously, no single policy can offer a panacea to Italy’s economic woes. But looking at the table below, which shows changes in wages for those on full time contracts since 1990, the issue does seem rather more clear cut than some are making out…

On Monday morning the BBC released a short documentary about the problem of clerical abuse in Italy. The film, which you can watch in full on YouTube, reveals a culture of “complicity and negligence” which conceals the true scale of the abuses taking place. Despite some rather sensationalist framing, Mark Lowen does a good job here explaining how hundreds of thousands of abuse cases have likely been concealed over the past few decades. The film is at its best when it patiently explains the layers of bureaucracy that have facilitated this; focusing in particular on the Lateran Pacts and legal autonomy of the Vatican’s canon law over Italian secular law. Sadly, some of the interviews are rather less successful - and I can’t help feeling the balance between survivors’ testimonies and institutional explanations was a little off. Still, caveats aside, this is an important ENG overview of a serious issue and well worth 20 minutes of your time. For more info, in Italian, I’d also recommend taking a look at the web platform featured in the film, Rete l’Abuso, which, in the absence of official statistics, is mapping trials that are ongoing across the country.

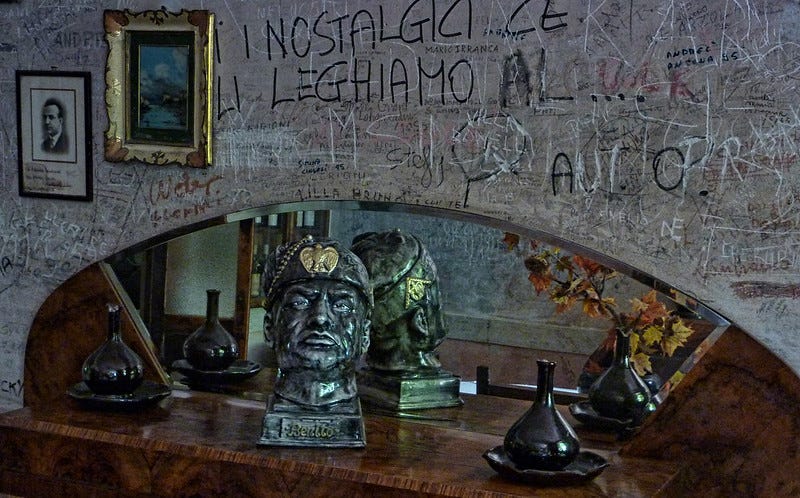

Lucy Hughes-Hallett, author of the wonderful The Pike: Gabriele D'Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War, has got a piece out in the TLS reviewing two new books about Italian fascism. The first, Blood and Power, by John Foot offers a chronological, materialist analysis of the rise and fall of the regime based on testimonies of those who lived under it. The second, by Francesco Filippi, Mussolini Also Did a Lot of Good: The Spread of Historical Amnesia, provides a more detached but meticulous fact-checking of the apparent ‘successes’ of the fascist state that regularly do the rounds on social media. Both of these books, by the way, are on my to read list, but here I really just want to encourage people to check out Hallett’s piece in its own right. It’s a brilliant little essay which synthesises the arguments of the two studies to deliver its own highly eloquent message about how the far-right are regaining cultural hegemony. Here’s the link.

Arts and culture: from the sublime to the ridiculous

I really enjoyed reading a long essay in The New Yorker this week about the Italian photojournalist Paolo Pellegrin. The piece is, to some extent, biographical, telling the story of Pellegrini’s approach to his work, his childhood fascination with art, his engagement with philosophy, mathematics, chess and, of course, the circumstances that led to his recognition at the World Press Photo awards on ten separate occasions (!) The author of the piece, Ben Taub, is a friend of the photographer so there’s real warmth and affection here (which already makes the story more interesting and intimate than your usual arts profile). The main narrative hook concerns Pellegrin’s “quiet struggle” against glaucoma and his constant fear of going blind. This provides a powerful human and existential anchor to the text but just as importantly it gives real insight into Pellegrin’s work and the manipulation of blurs, smudges, foggy patches and shadow that so characterise it. Read the essay here, and get ready to feast your eyes on some truly wonderful photos.

Kazumi Yoshida, the renowned Japanese contemporary artist and designer, has just opened a new show in Palermo. UTOPIA is a personal homage to the Sicilian capital, a city Yoshida has, apparently, fallen in love with over the years on account of its “art, nature, architecture and life-loving residents”. The exhibition is comprised of dozens of tapestries, paintings and sketches which the artist created between New York and Palermo while reflecting on the concepts of cosmopolitanism and hybridity that are so evident across the Mediterranean. Yoshida’s style is deeply rooted in the traditions of both botanical illustration and fashion design and his artistic influences include Jean Cocteau, Raoul Dufy, Fernand Léger, Marie Laurencin, Picasso and Matisse. The prospect of him applying his imagination to Sicily is therefore pretty intriguing, and I’m told the local public have responded positively so far too. The show runs until 30 July in the Loggiato San Bartolomeo; worth a visit, I reckon, if you happen to be in the area this summer.

Recipe of the week: broad bean favata with courgettes and tomatoes

This dish, which is eaten across the central and eastern Mediterranean, is one of my all time favourites of cucina povera. The base is a puree of dried broad beans - otherwise known as faba, baqella, fūl, haba or horse beans. Think of it as a kind of humus; a creamy smooth vegetable paste which can be used as a bed for various toppings. In Puglia this is usually served warm with wilted bitter leaves and a load of chili in winter; in Sicily, where it’s known as maccu, it’s eaten all year round, at varying temperatures with whatever sessional vegetables happen to be on hand. Rachel Roddy’s excellent version is closer to the second camp. She adds a potato to the puree, to ensure extra creaminess, and her vegetables of choice, tomatoes and zucchini, offer a nice sweet and sour contrast. You might want to add some grilled peppers in there, to take things in a more Turkish direction, or perhaps a little nduja for a modern pseudo-Calabrese touch. Personally, though, I like to serve this as it is - just below room temperature - to get the most out of the textures and flavours. Here’s the link.

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m an author, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. No worries if you can’t chip-in or don’t feel like doing so, but please do consider forwarding this to a friend or two. It’s a big help!