Today is 25th April. The Festa della Liberazione. Liberation Day. A moment when Italians remember the victory of the popular resistance against the Nazi-Fascist forces. It’s true, there are many (many) local anniversaries related to the end of the war and the toppling of Mussolini’s regime. But this is the most important nationwide public holiday dedicated specifically to the partisan struggle for democracy and freedom.

Much ink has been spilled on the chaos of late WWII Italian history. Scholars and political groups still argue over the precise composition of the anti-fascist movements; the comparative importance of different factions and the extent to which the resistance has constituted itself as a “myth”. Some contest the very nomenclature of the conflict’s resolution: suggesting that Italy was not “liberated” but simply “occupied” by U.S. and Allied forces from 1943 onwards. I’ve written on these competing claims many times before, and won’t be repeating myself here. The best source, anyway, for interested readers, remains Claudio Pavone’s inimitable first hand account Una Guerra Civile [also published in ENG as A Civil War: A History of the Italian Resistance.]

In this week’s edition I instead want to use this space to reflect on the legacy of 25 Aprile and the struggle against authoritarianism and tyranny today.

If you’re a regular reader you’ll know by now that the political situation here continues to deteriorate. While the country is in a quite different socio-economic state than it was in the regime-era of the 1920s and 1930s, living under a government which includes ministers who profess nostalgic admiration for Benito Mussolini is disconcerting to say the least. Indeed, many members of Giorgia Meloni’s administration refuse to celebrate 25 Aprile at all. Local councillors half-jokingly perform “Roman salutes”; provincial bureaucrats quote the fascist philosopher Giovanni Gentile. More worryingly — absurd, performative spectacle aside — this government is attacking various rights, threatening the independence of the judiciary and forcing an ultra-conservative “family-first agenda” on the public — policies which, together, demonstrate undeniable continuity with the far-right past.

One area in particular where alarm bells should be sounding regards freedom of expression. Meloni has been seeking to exert a tight control over the state media, RAI, and the cultural sector since day one of her government. She is a skilled and avid propagandist. She is also, one must add, paranoid, censorious, illiberal and increasingly incapable of confronting her critics. Over the past months, Meloni’s allies have raised legal cases against numerous public intellectuals and artists including the anti-mafia journalist Roberto Saviano and the Placebo singer Brian Molko (who, on stage, called the PM a “fascist, racist piece of shit.”) More recently still, this intimidation has spread to universities. As I write this, the philosopher Donatella di Cesare is facing a legal process for having referred to the Agriculture Minister Francesco Lollobrigida as a “neo-hitlerian.” Luciano Canfora, a historian, is also facing prosecutors for his remarks that Meloni has “the soul of a neonazi.”

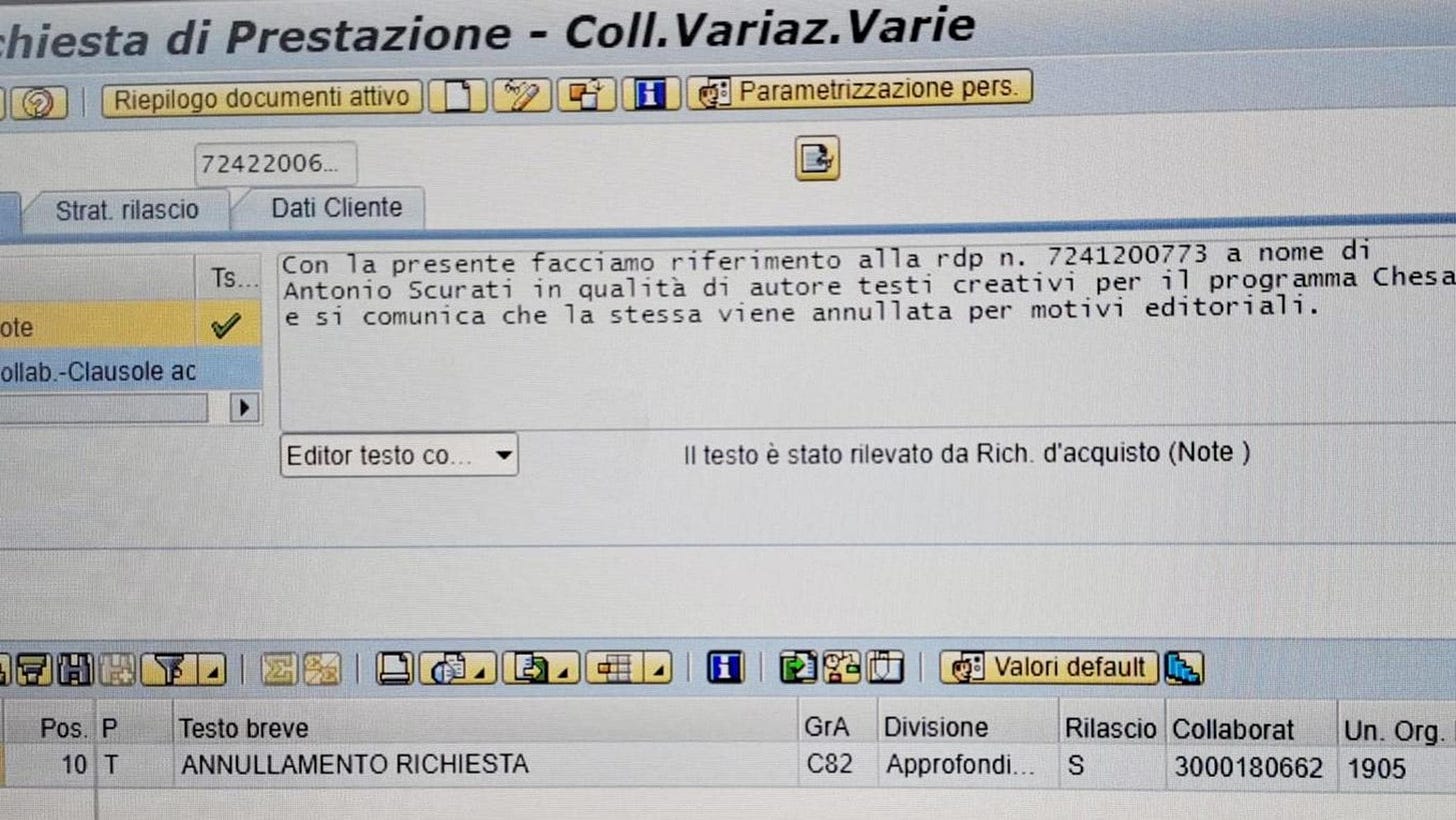

So where does 25 Aprile come into all this? Well, quite directly as it turns out. Last week, Antonio Scurati, author of the Premio Strega prize winning novel M: Son of the Century, was scheduled to deliver a monologue on RAI on the theme of anti-fascism and the Resistance today. At the last minute, however, the corporation pulled the segment without explanation. Meloni and her representatives insisted that the reason was entirely financial. "Scurati “asked for too much money,” they said. The author and his agent, however, suggested there were more sinister reasons behind the decision given that his contract had already been approved in line with previous rates. After much back and forth, including an intervention from Meloni herself, La Repubblica leaked an official letter confirming that the segment was indeed cancelled for “editorial” reasons. Put plainly: Scurati’s anti-fascist monologue was censored by the Italian state broadcaster.

In such a context, I can think of few more appropriate ways to mark the Festa della Liberazione 2024 than to share the full translated text of Scurati’s proposed intervention. The monologue itself, is… actually, well… as you’ll see, fairly mundane. The author provides a striking if relatively humdrum overview of the government’s recent attempts to sanitize the real violence of the fascist era. In itself, this doesn’t amount to much. The fact that RAI intervened to silence his voice, however, is without doubt a serious story in its own right, and a reminder that – in times of rising authoritarianism - we must all think about the ways we can stand up for free democratic expression in our work and in our lives more generally. In my case, among other things, that means a continued commitment to documenting and challenging the new fascism that is gathering pace in Italy, in this newsletter and beyond. So on that note: solidarity with Mr. Scurati, buon 25 Aprile a tutt* and more from me very soon.

*In keeping with the time-honoured Italian tradition of taking late spring labour day ‘ponte’ holidays, I’m about to head off for a short break. The Week in Italy will be back in your inbox, as usual, on 9 May!

**

Antonio Scurati’s Liberation Day monologue

Giacomo Matteotti was murdered by fascist hitmen on June 10, 1924.

Five of them waited for him outside his house. They were all squad members from Milan, professionals of violence hired by Benito Mussolini’s closest collaborators. The Honorable Matteotti, secretary of the Unitary Socialist Party and the last person in Parliament who still openly opposed the fascist dictatorship, was kidnapped in the centre of Rome, in broad daylight. He fought to the end, as he had fought all his life. They stabbed him to death, then disfigured his body. They bent him into two in order to fit him into a grave, badly dug out with a blacksmith’s file.

Mussolini was immediately informed. Along with this crime, he was guilty of the infamy of swearing to Matteotti’s widow that he would do everything possible to bring her husband back to her. While he was making this promise, the Duce of fascism kept the bloodstained documents of his victim in his desk drawer.

In this false spring of ours, however, we are not only commemorating Matteotti’s political murder. We are also commemorating the 1944 Nazi-fascist massacres perpetrated by the German SS, with the complicity and collaboration of the Italian fascists, those that were carried out at the Fosse Ardeatine, Sant’Anna di Stazzema and Marzabotto. These are just some of the places where Mussolini’s demonic allies massacred thousands of defenceless Italian civilians in cold blood. Among them hundreds of children and even infants. Many were even burned alive, some decapitated.

These two concomitant anniversaries of mourning – the Spring of 1924 and the Spring of 1944 – proclaim that fascism was, throughout its entire historical existence and not just at the end or occasionally, an irredeemable phenomenon of systematic political violence characterized by murder and massacres. Will the heirs to that history recognize it once and for all? Unfortunately, everything leads one to think that this will not be the case. The current post-fascist ruling group, having won the elections in October 2022, could have gone down one of these two paths: repudiate its neo-fascist past or try to rewrite history. It has undoubtedly taken the second path.

After having avoided the topic during the electoral campaign, Italian Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni , when forced to address it on the occasion of historical anniversaries, obstinately stuck to the ideological line of her neo-fascist culture of origin: she distanced herself from the indefensible brutalities perpetrated by the regime (the persecution of the Jews) without ever repudiating the fascist experience as a whole. She blamed the massacres carried out with the collaboration of Italian fascists on the Nazis alone. And finally, she ignored the fundamental role of the Resistance in the rebirth of Italy (to the point of never mentioning the word “anti-fascism” on April 25, 2023).

As I speak to you, we are once again on the eve of the anniversary of the Liberation from Nazi-fascism. The word that the Prime Minister refused to pronounce will still be quivering on the grateful lips of all sincere believers in democracy, be they on the left, center or right. Until that word – anti-fascism – is pronounced by those who govern us, the spectre of fascism will continue to haunt the house of Italian democracy.

Translated from the Italian by Masturah Alatas, with the author’s permission. First published in Counterpunch.

Antonio Scurati is a novelist, professor of comparative literature at IULM University – Milan and a columnist for Corriere della Sera. He won the Strega Prize for his novel M: Son of the Century (2018).

I’m Jamie Mackay, a UK-born, Italy-based writer, working at the interfaces of journalism, criticism, poetry, fiction, philosophy, travelogue and cultural-history. I set up ‘The Week in Italy’ to make a space to share a regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds, to explore politics, current affairs, books, arts and food. If you’re a regular reader, and you enjoy these updates, I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month. I like to think of it as a weekly catch-up chat over an espresso. Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. Grazie!