I want to start this week’s newsletter with a grim but important story. For three months now, since October 2021, a 55-year-old inmate in an Italian prison, Alfredo Cospito, has been on hunger strike to protest against conditions in a facility in Sardegna where he is being held under the “hard internment” law 41-bis. This is not the place to morally interrogate the man’s crime. Cospito is a green anarchist activist who was sentenced to over 10 years after shooting an administrative manager of a nuclear power plant in the knee in order “to prevent [what he saw as] an imminent new Fukishima”. The issue at hand, at least the one I want to draw attention to, is the nature of the punishment. 41-bis is one of the most severe penal laws in the EU. Judges introduced the clause in 1992 during a series of mafia bombings as a way of ensuring inmates would be unable to communicate with colleagues on the outside. “Harsh” is an understatement. Under 41-bis, prisoners are allowed just two hours’ exercise a day, ten minutes of phonecalls per month, or one visit. That’s it. The rest of their lives they spend in solitary confinement, and they are even forbidden from keeping photos in their cells. Amnesty has long argued that 41-bis is a violation of Human Rights, and bodies as diverse as the ECHR, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and even some members of Italy’s Constitutional Court have argued it should be re-written. Now, with Cospito on the verge of death (he’s lost 40 kilos in just three months), a debate is raging once again. Is this measure really essential to ensuring public safety? Or is it an unacceptable, even gratuitous form of torture? As the media cogs turn, and camps align in predictable fashion, I recommend reading this ENG piece at courthousenews to clue-up on the basic facts.

I’ve been banging on for some years now about the slow and steady rise of a new pan-European right wing movement, one that’s sovereignist in spirit yet perfectly adept at working across borders in a transnational manner. Italy has long been at the centre of this dynamic new conservatism, at least since 2018 when Steve Bannon and other macho alt-right American nerds settled on the Trisulti Monastery in Collepardo as a centre for their “gladiator school”. That particular venture failed, and the project was evicted in 2021, but in recent months, following the obvious catastrophe of Brexit, and other shifts in global geopolitics, sovereignist leaders seem to be have begun developing a new strategy to take control of Europe’s institutions. And Georgia Meloni is the key player. Don’t believe me? Well, this piece by Nicholas Vinocur and Jacopo Barigazzi, which POLITICO published earlier this week, offers a particularly concerning and convincing analysis of how the Italian government’s current regressive policy agenda fits into a bigger trend. According to the authors, since coming to power, Meloni has been consistently and successfully courting a number of influential “moderate conservative” figures in the EU such as Ursula von der Leyen and Roberta Metsola who, wittingly or otherwise, seem to be allowing her to set a new agenda for the continent. The ultimate goal, according to Vinocur and Barigazzi, is to secure a future coalition between the “centre-right” EPP and far-right ECR ahead of next year’s European Parliament elections. This is an alliance that, if successful, would stall any hope of a meaningful progressive EU politics emerging in the coming years – so liberals, centrists, socialists and greens alike really need to take note. Here’s the analysis.

A couple of weeks ago I shared a fascinating story by John Last about culinary nationalism and the future of Italian food which was published over at Noema magazine. Based on the response from various readers here, it seems to have struck a chord. Sticking briefly with that theme, then, I want to share a subsequent link for anyone that’s interested. Katie Parla and Danielle Callegari have long been covering food nationalism in a thought-provoking manner on their podcast GOLA. The latest episode - released this week - keeps with this trend by unpacking the broader picture of how Italian cuisine was created; particularly vis-a-vis the ‘migration’ of ingredients from the (scare quotes) “new” world. I’m sure most readers have a basic grasp on the essentials here. Tomatoes, potatoes, peppers all come from the Americas. We know already! Parla and Callegari, however, quickly move beyond the obvious examples to take some really interesting diversions, discussing niche ingredients (vanilla for example), exploring what Italian food looked like before colonisation, and reflecting on the thorny question of how colonial economics underpins contemporary tastes. Listen on Spotify here.

Arts and culture: Keeping it Real

Naples is without doubt one of the most cinematic, dramatic, theatrical, visual cities in Italy. It’s also, as I’ve written before, a victim (as a much as a beneficiary), of its own spectacularization. This is why I was particularly pleased to come across Victoria Fiori’s debut documentary this week, a film which seeks to confront easy stereotypes, and, in the words of one reviewer, “eschew sensationalised representations of Naples and its relation to the mafia and organised crime, opting instead for a more intimate vantage point that grants access to the very depths of the locality’s psyche.” Fiori’s documentary follows Entoni, a young boy who, like far too many others, finds himself confined to a juvenile detention centre for committing a petty crime. Rather than demonizing or glamorizing her subject Fiori seeks to build a bond of trust and collaboration with Entoni that ultimately allows her to capture his personal, human story while also offering a real truth about poverty and violence in the south: “instead of providing the necessary support to underprivileged children trapped in generational cycles of incarceration, the Italian state chooses to criminalize their behavior.” Check out this LWL review for more details.

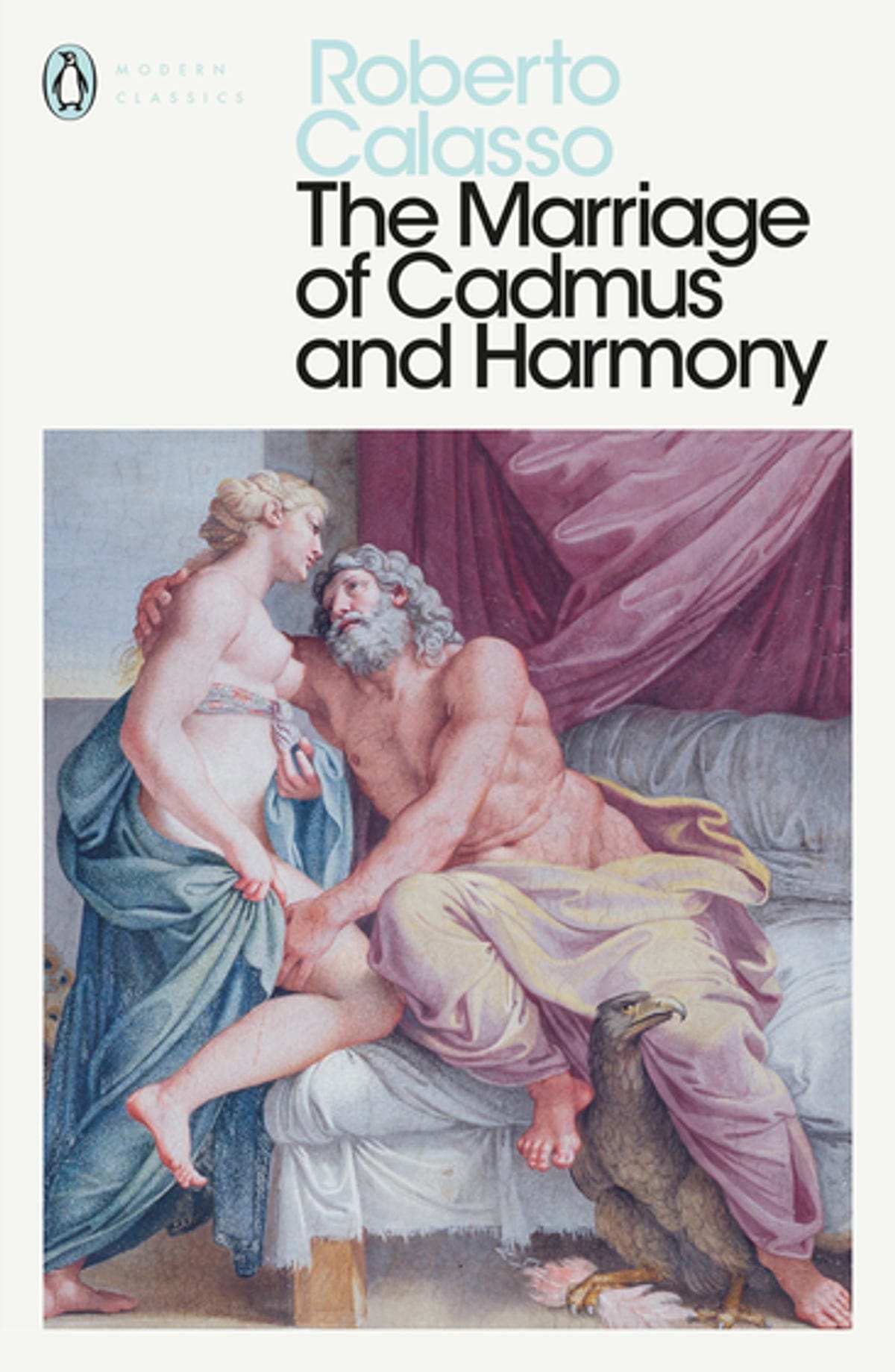

I’ve written a few times about Roberto Calasso and his work both as an author and, just as importantly, as an editor and publisher at Adelphi editions. If you haven’t read The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony or The Ruin of Kasch – which were both translated into English in the 90s - what can I say except: do it, add them to your list. Calasso’s work changed my life, and particularly the way I see the links between mythology, arts, culture, politics and history. He was a modest, clear-sighted and poetic writer and a great synthesizer of global anthropological trends. This week, the Romanian-American philosopher Costică Brădățan published an interesting retrospective essay about Calasso’s work that made me think about his writing in a new light once again. In his piece Brădățan presents Calasso as a product of the Italian system of humanist education “(still one of the best anywhere)” yet at the same time its greatest critic: “someone who realized that a sterile academic imprint could be dangerous to the more open-minded.” For Brădățan, Calasso’s ultimate task was not intellectual in any conventional sense, but ultimately spiritual: his writing aimed to re-enchant the world, to re-position myth as a vehicle for self-understanding, to shape excess into sacrifice and, by extension, creativity. It’s an interesting, if niche, interpretation - but a good one to ponder as and when you find yourself in a reflective, meditative mood. Here’s the link.

Recipe of the week: Blackened chicken with caramel and clementine dressing

OK this dish is by no means ‘traditional-Italian.’ In fact, it’s not even – really – Italian at all but rather a pan-Mediterranean assemblage taking in influences from Sicily, North Africa and even, at a push, East Asia. The recipe is part of Ottolenghi’s Test Kitchen series (which is, of course, mainly authored and created by a team of female chefs from around the world, e.g. Ixta Belfrage, who sell their work to the overhyped maestro but let’s not go there.) The point is, if you eat meat, you really have to try this. The chicken is charred and smokey; pan-cooked but with an almost BBQ grilled flavour. The sauce is sweet and sour, perfectly balanced and with a certain indefinable nomadic intrigue. The surprising star(s) of the show, however, at least in my book, are the spring onions which melt down into long, earthy umami strips and, ultimately, bring the whole plate together. This is a simple recipe but it tastes extremely, almost unbelievably, refined. So check out the YouTube video below, and give it a go to create some genuine restauranty flavours at home. Click here for some extra, written instructions.

About Me

My name is Jamie Mackay (@JacMackay) and I’m an author, editor and translator based in Florence. I’ve been writing about Italy for a decade for international media including The Guardian, The Economist, Frieze, and Art Review. I launched ‘The Week in Italy’ to share a more direct and regular overview of the debates and dilemmas, innovations and crises that sometimes pass under the radar of our overcrowded news feeds.

If you enjoyed this newsletter I hope you’ll consider becoming a supporter for EUR 5.00 per month (the price of a weekly catch-up over an espresso). Alternatively, if you’d like to send a one-off something, you can do so via PayPal using this link. No worries if you can’t chip-in or don’t feel like doing so, but please do consider forwarding this to a friend or two. It’s a big help!